It’s been a rainy August on the Colorado Plateau. Afternoon thunderstorms chisel sandstone cliffs and buttes, sending millions of years sloshing downhill as sediment suspended in water. This aquatic rearrangement of time follows a dendritic path of least resistance, and the desert becomes a network of coalescing canals more complicated than any human city.

Eventually the water pools and slows, and the sediment it carries creates submerged clouds. These plumes of ancient sand, dust, mud, and stone knead one another and become an unmistakably brilliant kaleidoscope below the river’s surface. Then they sink, settle, and sit. Overnight the environment is transformed, permanence permeated by water, the Earth’s history rewritten by erosion, and we are left to observe, contemplate, and attempt to understand the poetry of time and space.

I found myself similarly cast from rest into motion as I drove towards Salt Lake City in September to attend a wedding on the East coast. The humble two-lane road through Green River became a tributary to the state highway, which then came to a confluence with into the interstate. Along the way, the asphalt aqueduct became more saturated by stuff—cars, trucks, billboards, buildings—and time seemed to speed up.

Dirt and water and rock gave way to metal and plastic and concrete—organic becoming inorganic, natural becoming unnatural, scenes becoming screens. Then I boarded a flight bound for New York City, and as we climbed thousands of feet above the canyons I had floated through just days before, things slowed down once more, and thoughts began to settle out of my turbulent mind.

During my travels, I spent time with some friends who went down Desolation canyon with Holiday this Summer. They shared similarly stirring experiences upon re-entering civilized society after a week spent in the wilderness, and they explained that it all started with the grief and hesitation that I so often see show up on the last day of a river-trip, when the prospect of returning home becomes reality. We all agreed that a wonderful peace-of-mind seems to be found out there and then subsequently lost.

So, we got to thinking and set out to distill the drivers of this serenity, so that we could devise ways of preserving it when you can’t just hop into a boat and head downstream. Think of the components we came up with like sliders in a control room. You’re the operator and the outcome is your sense of wellbeing. It’s not about drastically changing anything. The goal is just to shift some things from one end of the spectrum towards the other, and by doing so, reclaim the peaceful contentedness and childlike joy that we often regret losing when the river is in the rearview mirror.

Slow down

Off the river, in civilization, we’ve turned time into a quantifiable resource to be harvested. To do this, we invented clocks and calendars to standardize and track time, and we redefined both work and leisure to revolve around hours spent on specific tasks. This is why we now have an entire self-help industry dedicated to helping us optimize how we spend our time. As a result, most of us tend to prioritize speed and efficiency as inherently good without even realizing it.

But this creates in an invisible sense of pressure, that nagging feeling that there just aren’t enough hours in the day, that maybe we ought to be spending our time differently. Even that language, "spending" time and its opposite "wasting" time, reinforce the notion that time is a finite resource that you’re throwing away if you’re not constantly doing. What would your life look like if you stopped trying to measure and use time to do and focused instead on just being?

It sounds like a radical idea, but this is exactly what happens to us on the river. You wake up in the morning to our "Hot Coffee!" call, eat when you’re hungry, and go to sleep when you’re tired. In the space in between, you move slowly and intentionally, do whatever you most want to do, and feel no pressure to be doing anything except what you already are. I also encourage guests to stash their phones and watches in the bottom of a bag for the duration of the trip, to really embrace the idea that time as a quantifiable resource no longer exists, and as Heidegger argued, we don’t have time, we are time.

Off the river, living like this is much harder, especially if you’re participating in an economic system that Oliver Burkeman describes in Four Thousand Weeks as "a giant machine for instrumentalizing everything it encounters—the earth’s resources, your time and abilities (or "human resources")—in the service of future profit." But we can always shift away from instrumentalizing our time by choosing to slow down and savor the pleasures of the present moment, whether that’s a flavor, scent, sight, sound, thought, or feeling.

If we do this, we must also avoid the trap of turning "being in the moment" into a quantifiable activity at which we can succeed or fail at based on how long we manage to do it. That’s why I prefer the simple idea of just slowing down instead of the more nebulous suggestion that we should let go of needing to do anything at all.

For example, when I was in college I flew to Tanzania and climbed Mt. Kilimanjaro. I was an over-ambitious sophomore and my motto for the expedition was "summit or bust." After hearing this, the local guides on my trip pointed out that I’d flown around the world for the adventure of a lifetime and yet somehow seemed eager to get it over with as quickly as possible. They found this both funny and tragic, and made it a habit to regularly remind me "pole pole," which translates from Swahili as "slow slow."

So, how can we move the slider from fast to slow in our busy lives? How about intentionally being idle for a while every morning, starting each day with a cup of coffee and a book, away from clocks and calendars and oblivious of any need to achieve or progress, focused instead on finding joy in the current moment. Then, we can carry this state of mind into the day, so that when it does become necessary between 9 and 5 to remain aware of time, and the stress begins to set in, we can remember that there’s another way of being, waiting for us once again in the evening.

Reduce distractions to stay present

Our constructed sense of time isn’t the only thing trying to pull us out of the present moment. As nun and author Pema Chödrön explains, "all of us derive security and comfort from the imaginary world of memories and fantasies and plans. We really don’t want to stay with the nakedness of our present experience. It goes against the grain to stay present." Now, it’s easier than ever before to disappear to an imaginary world with the push of a button, and once we’re there, it can be incredibly difficult to come back.

This isn’t our fault. Nor is it an issue of self-control. An entire industry has arisen around the commodification of our attention, and therefore we’re constantly subjected to powerful attempts to capture and sell our attention. Like most new technology, this seemed benign at first, but we now understand the pernicious effects of letting billion-dollar companies profit from keeping our minds captive in imaginary worlds.

At risk of sounding like a luddite, I don’t think that technology and social media are entirely bad. There is inherent value in visiting imaginary worlds every now and then to seek inspiration. But that’s not the business model these companies have adopted. They are not trying to inspire us. They are trying to hold us hostage, weaponizing years of psychological strategies to invoke extreme emotional reactions and recognize our emotional states in order to take advantage of them.

As a child of the internet era, I’ve always wondered what a world without smartphones was like; what it would have been like to sit in a public space surrounded by people whose eyes weren’t glued to screens. Trying to experience this is especially hard, because even if you successfully break free from the grasp of screens and sounds that are constantly trying to capture your attention, it’s nearly impossible to find places where everyone around you has also done the same.

Which brings us back to the river, where no-technology is the norm. Far from cell service and electricity, everyone is forcibly freed from most common forms of distraction, and the result is rich connection and meaningful conversations. I’ve watched in awe as people with drastically different worldviews become lifelong friends because they’re both fully present and therefore focused on listening, understanding, and connecting. I’m also struck by how many things they inevitably begin noticing about themselves, others, and the world around us once the feeling of presence settles in.

This seems to be something our brains deeply crave, and while scrolling through reels might feel good in the way a greasy burger does, deeply connecting with the people and places in front of us seems to feed our souls the nutrients they really need. So, whether it’s turning off notifications, making weekends phone-free zones, abandoning social media altogether, or seeking out communities that don’t involve devices, there are many ways we can defend ourselves from distractions. As one of my guests from a Spring Yampa trip explained when I asked him about his return from the river:

It was like exiting a strange and wonderful dream with a new perspective on life. I became an avid observer of the world around me. I was present. I walked the streets and rode buses and saw people and thought about them, how they had entire lives just as complex as mine, hopes and dreams, love and yearning, and how they deserved just as much patience and kindness as I gave to myself. The biggest factor in making that aura last beyond the trip was staying off my phone. I wrote down to-do lists on notepads, journaled when I was bored, and talked to people with kind and curious eyes. Staying off my phone led me to engage with the world and people around me in a more human way, in a more meaningful way. To maintain this beyond a few weeks was difficult, and I slowly did go back to my old habits for the sake of efficiency, because it is easier to keep to yourself, but I don’t think the impact of those weeks, beginning with the trip, is lost. The trip changed me for good, and I am a better human being for it.

Pursue simplicity and reduce complexity

Off the river, we are often faced with multi-step, complex, and ambiguous problems. In a world where we can no longer fend for ourselves, we depend on other people and organizations for goods and services, and in a global, digital economy this means that things can quickly get convoluted.

That’s not to say that we aren’t capable of troubleshooting a broken Wi-Fi router, applying for healthcare through the government marketplace, or managing multiple inboxes, but our minds certainly aren’t designed for it, and that means we ought to cut ourselves a bit of slack when complicated challenges like this inevitably wear us down. Like trying to eat steak with a spoon, we’re asking our brain to complete a lot of tasks it wasn’t designed to do, and while we can get away with it most of the time, it does come at a cost.

On the river, things are different. If you’re hot, you jump in the water. If you’re cold, you put on a jacket. You’re faced with simple, one-step, clearly defined problems with an immediately measurable solution, and this feels really good. While there’s always going to be some baseline complexity in our civilized world, there are a few things we can do to bring the simplicity of the river home with us.

First, you can decide to only do three things well every day. In other words, when you wake up, pick three things that you’re going to accomplish that day, and then set out to complete them before doing anything else. Afterwards, if you have leftover time and energy, you can continue getting stuff done, but by then it’s just a cherry on top. I’ve found this helps alleviate the pressure my to-do-list is constantly putting on me, and although it doesn’t actually reduce complexity, it helps me limit my mental aperture and ignore complexity that otherwise would be occupying my mind.

Second, you can buy fewer but higher-quality products. This has become especially hard in the era of "one-click purchases," overnight shipping, and targeted advertising, but one simple tool seems to make a huge difference: the wish list. For example, whenever I think I really want or need something, rather than buying it, I add it to my list. Then, if I think of it again, I go to the list and add a tally next to it. Eventually, one of two things happens: either I keep thinking about it and decide to go ahead and get it, or—and this is the case about 95% of the time—I forget about it entirely.

Third, you can opt for services over products when possible. For example, if you only need a drill once every few years, pay to rent it or hire someone rather than buying one and letting it collect dust in your garage next to thirty other things you probably don’t need to own. I’ll admit that this can be hard when it means passing up a great deal, but that’s where we can introduce a new metric into our decision-making: does it simplify my life?

Finally, and this is much easier if you’re already slowing down and trying to reduce distractions, you can commit to doing fewer but more fulfilling things. Some level of excess, stress, and complexity is inevitable, but I’ve been as guilty as anyone of intentionally seeking this out because it distracted me from the fact that deep down, I didn’t really know what I wanted to do. Thankfully, we all have a built-in compass to point us in the right direction: does it bring me joy? By doing more of the good and less of the bad, which often requires going against the grain and having the courage to be disliked, we can continue to focus in on what our hearts most desire and let go of anything we’ve been hanging onto that doesn’t align with this direction.

Reawaken your creative side

According to life coach and sociologist Dr. Martha Beck, the opposite of anxiety isn’t calm, it’s creativity. Consider this. If something scares you and you try to gain control, you get anxiety, but if instead you respond to it with curiosity, you get creativity. The two cannot co-exist, so it’s either one or the other.

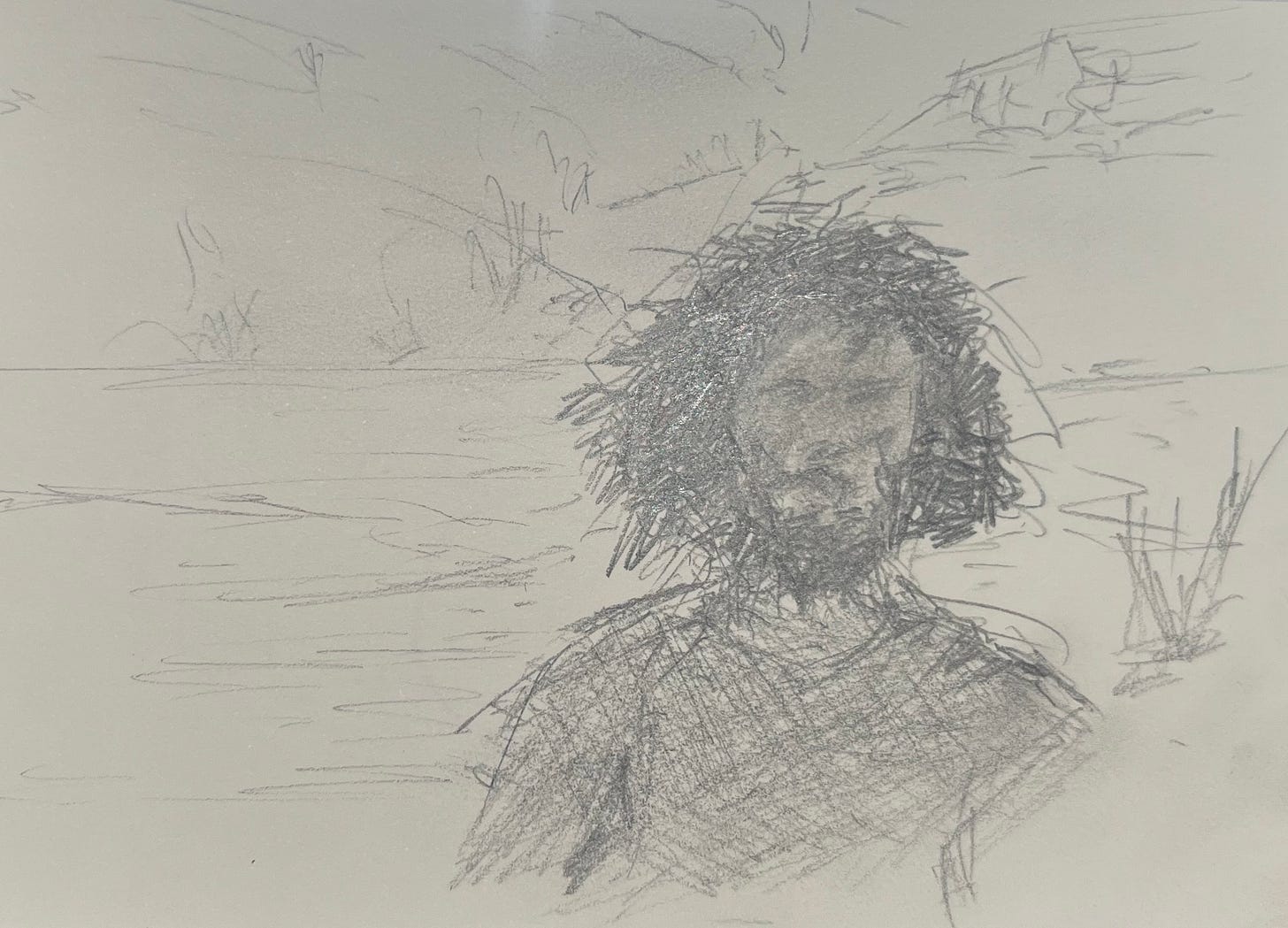

On the river, the fact that the guides are constantly in control of everything makes it mandatory for guests to go with the flow. Sometimes it takes people a few days to accept being out of control, but almost everyone comes around to it by the end of a trip. As a result, people begin to get curious about what could otherwise be a new environment with a lot of scary unknowns, and creative expression begins to emerge from that curiosity in the form of observing, writing, drawing, singing, moving, and more.

Off the river, it’s harder to go with the flow in such an individualistic society where you almost always have to be in control, and it’s impossible to choose curiosity and creativity all the time unless you’ve got access to unlimited resources. However, there are places where you can temporarily exchange control for creativity. I think this is one reason guided workout classes have become so popular, and why many people love working out with an instructor but struggle to do so alone. When you’re in the class, you’ve given up any need to control what happens, and instead you can focus on being curious and creative.

I’ve also seen people do this by cultivating their own creative practice. For one friend, this is excessively detailed Strava posts. For another, it’s drawing comics of the fun things that happen every day. For another, it’s playing the guitar. The common denominator between all these things is that they tap into our genuine curiosity about the unknown and enable us to make something with whatever we find. Seeking opportunities to regularly do that is a great way to move the needle in the right direction.

Prioritize community

In 2016, I lived in a tiny village in rural Ghana for two months without running water, electricity, air conditioning, or flush toilets. This was intimidating at first, but much like being on the river, I quickly came to understand that none of that really mattered, and given enough time, our bodies remember that these things are niceties not requirements for a good life. What is a requirement? Community. And that was abundant in the village.

I’ve since searched for and struggled to find spaces that shelter the interdependence in community I found there. Places where people matter more than things. The river is a bastion of what this looks like at its best. If anyone isn’t washing their hands, we will all get sick. If anyone falls out in a rapid, it’s up to us and only us to save them. As a result, we quickly recognize that we must depend on those around us, and that they are depending on us, which creates a sense of mutual care and accountability that feels deeply fulfilling.

Off the river, most of our modern world has become hyper-focused on the individual. This has its perks for sure—greater freedom and comfort—but it has also made genuine communities much harder to find. While group workout classes like CrossFit, cooperative housing arrangements, and local groups that regularly meet about a specific hobby might work for some of us, we can also create authentic communities ourselves.

I have a few friends who have begun hosting weekly dinner parties for this purpose. Everyone is responsible for not only bringing a dish, but also sharing something creative they’ve been working on. It doesn’t need to be fancy. Everyone just needs to know that they are contributing to and responsible for the wellbeing of the group. Once there, regardless of what you brought, you are treated like you matter and belong simply because you showed up. That’s key, because genuine communities are centered on love, kindness, and care like we experience on the river.

Spend time around non-human things

The last component that makes river trips feel so good, at least according to our best attempts to distill an ooey gooey state-of-mind into an actionable strategy, is the proximity to non-human things. This includes not-only non-human organisms, but also inorganic things like rocks and water and wind. These things remind us that our lives and issues and aspirations are ultimately insignificant in the grand scheme of the cosmos.

While this might sound like a bad thing at first, it’s liberating when you realize that the non-human world grants us a perspective on impermanence and reminds us that everything is constantly changing. This helps us take ourselves less seriously, stop worrying, and let go of needing to control what happens to us—recognizing that no matter what we do as an individual or species, we are and will always be woven into the fabric of the universe, intimately connected to something infinite and eternal.

On a recent Desolation canyon trip, I had a guest start each morning by reading a poem from Mary Oliver. I go down to the shore seemed to capture this phenomenon:

I go down to the shore in the morning

and depending on the hour the waves

are rolling in or moving out,

and I say, oh, I am miserable,

what shall—

what should I do? And the sea says

in its lovely voice:

Excuse me, I have work to do.

Whether it’s adding more plants to your office, going for a walk in the park every day, or switching from plastic cutting boards to wood ones, I think there’s immeasurable value in replacing human-made objects with natural ones; in regularly spending meaningful time around non-human lifeforms that help us view our own lives from a new perspective. While a river running through ancient rocks does this in a quick and obvious way, anything non-human in its origin has the same potential to comfort and ground us with the truth that we’re part of something much bigger than ourselves.

A closing challenge

I’ll concede that it’s easier to slow down, stay present, live simply, act creatively, exist in community, and spend time around non-human things during a river trip. At the same time, I know through experience that it’s possible to replicate many of these elements off the river. Doing so can be hard at first, but if we stick with it, it will bring our hearts, bodies, and minds back into harmony with how they were meant to be.

As a recent guest of mine from a Fall Cataract canyon trip explained, "everything else feels fake compared to this. Things out here just feel so real." But the real is out there too, we just need to subvert the stuff in our culture that makes it hard to find. So, next time you’re craving some more joyful serenity, in addition to signing up for another Holiday trip, I encourage you to try using these six sliders to refocus your time and energy on the little things:

As I look back o’er times that are past,

And fond memories I recall,

It’s the little fleeting things that last.

Important things are usually small.

Dreaming back through many years

Of both happiness and despair

The taste of salty tears—

A caress on silken hair.

Laughter on a moonlit walk

Over some silly little rhyme—

Time when there was no need to talk

A hand tucked snug in mine—

A twinkle in mischievous eye

Above a wrinkled nose

Memory of a tender sign

Sweet breast that fell and rose—

So the things that I recall,

The sweetness and the pain,

To some would matter not at all.

They think of worldly gain.

Should someone ask, "What have you done?

What accomplishments are there to see?"

Why, I saw a boat a rapid run,

And Michelle smiled at me.

-Vaughn Short

Many thanks to my friends and fellow guides at Holiday who helped me learn to live this way, and to the many guests and friends who’ve joined me on the river and spent hours trying to tack words onto the ways that being out there together made us feel.

What do you think? I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments or by replying here! Liked this essay? Please consider sharing it with someone else who might also enjoy reading.

Matt, you have some serious Forrest Gump vibes going on in that last photo of you! Btw, my parents are moving from Jackson, WY to Salt Lake City. We should try to coordinate a meetup whenever I visit them next!

Matt, I just found this through the LinkedIn algorithm somehow. What an essay! Thank you. A month into a new desk job, and too many months away from the river, I needed this as a reminder and prompt for keeping the truths of river life alive for myself. It’s scary how fast they can get lost. Thank you again for sharing! (And hi from San Diego!)